Why Are Permissions Important?

Permissions are important for keeping your data safe and secure. Utilizing permission settings in Linux can benefit you and those you want to give access to your files and you don’t need to open up everything just to share one file or directory (something Windows sharing often does). You can group individual users together and change permissions on folders (called directories in Linux) and files and you don’t have to be in the same OU or workgroup or be part of a domain for them to access those files. You can change permissions on one file and share that out to a single group or multiple groups. Fine grained security over your files places you in the driver seat in control of your own data.

Some will argue that it may be too much responsibility…that placing this onto the user is foolish and other aforementioned operating systems don’t do this. You’d be right…XP doesn’t do this. However, Microsoft saw what Linux and Unix do with the principle of least privilege and have copied this aspect from them. While the NTFS filesystem employs user access lists with workgroups and domains…it cannot mirror the fine grained, small scale security of Linux for individual files and folders. For the home user, Linux empowers control and security.

I’m going to go over how users and directory/file permissions work. So, let’s setup an example that will allow us to explore file permissions. If you have any questions, just ask it in the comments section at the end of the article.

File Permissions Explained

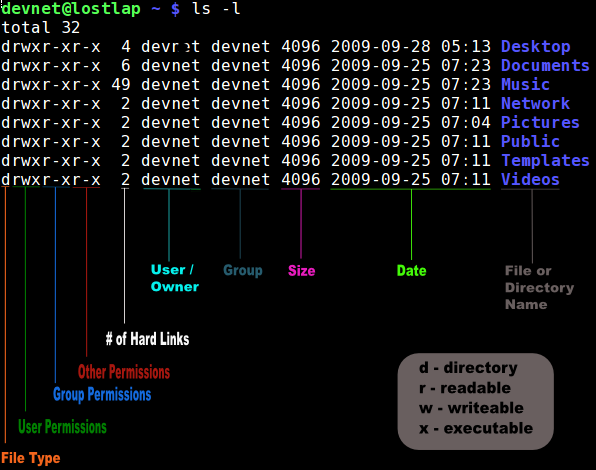

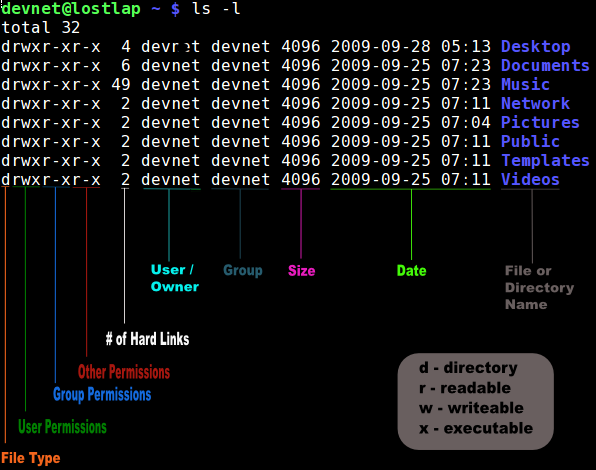

The picture to your left is a snapshot of my $HOME directory. I’ve included this “legend” to color code and label the various columns. Let’s go through the labels and names of things first and then work on understanding how we can manipulate them in the next section.

The picture to your left is a snapshot of my $HOME directory. I’ve included this “legend” to color code and label the various columns. Let’s go through the labels and names of things first and then work on understanding how we can manipulate them in the next section.

As noted in the picture, the first column (orange) explains whether or not the contents listed is a directory or not. If any of these happened NOT to be a directory, a dash (-) would be in place of the d at the beginning of the listing on the far left.

In the second, third, and fourth column (Green, Blue and Red) we find permissions. Looking at the gray box in the bottom-right corner gives us an explanation of what each letter represents in our first few columns. These tell us whether or not each user, group, or other (explained in detail later in this article) have read, write, and execute privileges for the file or folder/directory.

In the 5th column (white) the number of hard links is displayed. This column shows the number of actual physical hard links. A hard link is a directory reference, or pointer, to a file on a storage volume that is a specific location of physical data. More information on hard links vs. symbolic (soft) links can be found here.

In column 6 (light blue) we find the user/owner of the file/directory. In column 7 (gray blue), the group that has access to the file/folder is displayed. In column 8 (pink), the size of the file or folder is shown in kilobytes. In column 9 (fluorescent green), the last date the file or folder was altered or touched is shown. In column 10 (grey), the file or directory name is displayed.

We’re going to pay specific attention to the first four columns in the next section and then follow that up by working with the sixth and seventh by going over user/owner and group. Let’s move on to go over all of those rwx listings and how we can make them work for us.

Read, Write, Execute – User, Group, Other

First, let’s go over what different permissions mean. Read permission means you can view the contents of a file or folder. Write permission means you can write to a file or to a directory (add new files, new subdirectories) or modify a file or directory. Execute permission means that you can change to a directory and execute ( or run ) a file or script for that file or directory.

The User section shown in green in the picture above shows whether or not the user can perform the actions listed above. If the letter is present, the user has the ability to perform that action. The same is true for the Group shown in blue above…if a member of the group that has access to the file or directory looks in this column, they will know what they can or can’t do (read,write, or execute). Lastly, all others (noted in the red column above). Do all others have read, write, and execute permissions on the file or folder? This is important for giving anonymous users access to files in a file server or web server environment.

You can see how fine grained you might be able to set things up with…For example, you may give users read only access while allowing a group of 5 users full control of the file or directory. You may want to switch that around. It’s entirely up to you how you want to setup permissions.

More about Groups

Let’s go through setting up a group and adding a few users to it and then assigning that group permissions to access a directory and file.

Create a file inside your home directory by opening up a shell or terminal and typing:

touch ~/example.txt

You’ve now created a file called example.txt inside your home directory. If you are already there, you can list the contents with the ‘ls’ command. Do that now. If you’re not already there, type ‘cd ~/’ and you will be taken to your home directory where you can ‘ls’ list the files. It should look similar to the following:

[devnet@lostlap ~]$ ls -l

total 40

drwxr-xr-x 2 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-24 17:04 Desktop

drwxr-xr-x 6 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-24 13:10 Documents

drwxr-xr-x 9 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-27 15:25 Download

-rw-rw-r-- 1 devnet devnet 0 2010-05-28 10:21 example.txt

drwxr-xr-x 13 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-26 16:48 Music

drwxr-xr-x 3 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-24 13:09 Pictures

drwxr-xr-x 3 devnet devnet 4096 2010-05-24 13:04 Videos

Next up, let’s create a new group and a couple of new users. After creating these we’ll assign the users to the new group. After that, we’ll move the file and lock it down to the new group only. If everything works as planned, the file should be accessible to root and the other 2 users but NOT accessible to your current user. You’ll need to be root for all of these commands (or use sudo for them). Since I have sudo and don’t want to continually type sudo, I used the command “sudo -s” and entered my root password to permanently log in as root in a terminal for the duration of this how-to. OK, Let’s get started:

[root@lostlap ~]$ useradd -m -g users -G audio,lp,optical,storage,video,wheel,games,power -s /bin/bash testuser1

[root@lostlap ~]$ useradd -m -g users -G audio,lp,optical,storage,video,wheel,games,power -s /bin/bash testuser2

The above commands will create two users that should be pretty close to your current logged in user (as far as group membership goes). If the groups you’re adding the user to do not exist, you may get a warning that the groups don’t exist…no worries, just continue. If the above commands don’t work on your system (I used Arch Linux to do this) then you can use the GUI elements to manage users and add a new one. You won’t need to add them to any extra groups since we just need a basic user. Next, let’s create our ‘control’ group.

[root@lostlap ~]$ groupadd testgroup

The above command creates the ‘testgroup’ group. Now let’s add the two users we created to this group.

[root@lostlap ~]$ gpasswd -a testuser1 testgroup

[root@lostlap ~]$ gpasswd -a testuser2 testgroup

The command above adds both our test users to the test group we created. Now we need to lock the file down so that only those users inside of ‘testgroup’ can access it. Since your current logged in user is NOT a member of ‘testgroup’ then you shouldn’t be able to access the file once we lock access to that group.

[root@lostlap ~]$ chgrp testgroup example.txt

The above command changes the group portion of file permission (discussed earlier) from a group your currently logged in user is a member of to our new group ‘testgroup’. We still need to change the owner of the file so a new terminal opened up as your current user won’t be the owner of example.txt. To do this, let’s assign example.txt a new owner of Testuser2.

[root@lostlap ~]$ chown testuser2 example.txt

Now when you try to access the file example.txt you won’t be able to open it up as your standard user (root still will be able to access it) because you don’t have the permissions to do so. To test this, open up a new terminal (one where you are not root user) and use your favorite text editor and try to open up example.txt.

[devnet@lostlap ~]$ nano example.txt

Both testuser1 and testuser2 will be able to access example.txt because testuser2 owns the file and testuser1 is in the testgroup that has access to this file. However, your current logged in user will also have READ rights to it but will not be able to access it. Why? Let’s take a look at the permissions on example.txt

[devnet@lostlap ~]$ ls -l example.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 testuser1 testgroup 8 2010-05-28 10:21 example.txt

Notice that the user, group, and other (1st, 2nd, and 3rd position of r,w,x – see the handy diagram I made above) have permissions assigned to them. The user can read and write to the file. The group can read it. Others can also read it. So let’s remove a permission to lock this file down. Go back to your root terminal that is open or ‘sudo -s’ to root again and do the following:

[root@lostlap ~]$ chmod o-r example.txt

Now go back to your user terminal and take a look at the file again:

[devnet@lostlap ~]$ ls -l example.txt

-rw-r----- 1 testuser1 testgroup 8 2010-05-28 10:21 example.txt

Once that has been accomplished, try and open the file with your favorite text editor as your currently logged in user (devnet for me):

[devnet@lostlap ~]$ nano example.txt

Your user now should get a permission denied error by nano (or whatever text editor you used to open it). This is how locking down files and directories works. It’s very granular as you can give read, write, and execute permissions to individual users, groups of users, and the general public. I’m sure most of you have seen permissions commands with 777 or 644 and you can use this as well (example, chmod 666 filename) but please remember you can always use the chmod ugo+rwx or ugo-rwx as a way to change the permissions as well. I liked using letters as opposed to the numbers because it made more sense to me…perhaps you’ll feel the same.

Hopefully you now have a general understanding how groups, users and permissions work and can appreciate how the complexity of it is also elegant at the same time. If you have questions, please fire away in the comments section. Corrections? Please let me know! Thanks for reading!